Toobin is back: Fallout from The New Yorker's Zoom call from Hell and other pandemic delights

The journalism superstar's behavior last fall is a case study in how work and personal lives collided during the pandemic

CNN welcomed journalist Jeffrey Toobin back to its broadcasts late last week, roughly eight months after The New Yorker fired him for accidentally exposing himself during a Zoom staff meeting.

This would be totally unremarkable, except Toobin's misstep is an unmitigated case study of how our careers, aided and abetted by Zoom and Microsoft Teams, overran and occupied our homes during the pandemic.

It's also true that Toobin's situation was handled dreadfully — as though it had been thrown to a chittering huddle of middle schoolers who failed to recognize that his conduct had more to do with the circumstances brought by the pandemic than it did his character.

Toobin appeared on CNN late last week for the first time since October and, in an interview with Alisyn Camerota, apologized, then explained what went wrong.

"I didn't think I was on the call. I didn't think other people could see me," Toobin said. "I thought I had turned off the Zoom call. Now, that's not a defense. This was deeply moronic and indefensible. But that is part of the story."

In other words, Toobin is more guilty of not knowing how to use Zoom than he is of a moral failing. He thought he was in the privacy of his own home. He wasn't.

The New Yorker suspended then fired Toobin following the incident. He took a break from CNN, too, until the network allowed him to return as its chief legal analyst last week.

Since October, Toobin has been the subject of public ridicule, including no less than two Saturday Night Live sketches. Late night talk show hosts have had a field day. All of which, I suppose, is to be expected.

Still, I keep asking myself, if Toobin didn't intend for anyone to see him, why is this a story? Possibly because there are those who don't believe Toobin. Possibly because there's more to the story than we know. Possibly because we’re all middle schoolers when it comes to this sort of thing. And possibly because the experience of being on that call was so horrific that, regardless of Toobin's intentions, it can't be excused.

There's no question the October incident wreaked pure terror on everyone involved – not the least of which Toobin, a 27-year veteran of the magazine who has authored seven books, including "The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court."

His colleagues described briefly seeing Toobin touching, um, the area his bathing suit covers. And there's some indication that his actions might have amounted to a flirtatious joke intended for someone else. Witnesses said they saw Toobin blow a kiss to someone other than his colleagues. Toobin then left the call. He logged back on moments later, seemingly oblivious to what everyone else had seen.

Every morning, still barely conscious, I open a can of cat food for our two cats, Tracer and Iggy Pop. It smells horrible, and if I get a whiff of it at the wrong moment my body shudders and I sometimes dry heave. That's how I feel when I think about what it must have been like to be on that New Yorker call – more because of the shock and embarrassment than anything else.

Editor David Remnick was surely left with no choice but to end the meeting, summon HR with bright, glowing shot fired high from a flare gun and then give everyone a time-out to burn sage, call their priest or drink heavily — whatever it took for The New Yorker's staff to find its happy place again.

Toobin, meanwhile, must've felt like a dog hit by a car. I'm sure he wanted to crawl off somewhere dark and die.

He’s described the time since the incident as the "most miserable months in my life" and said he's been "trying to be a better person."

"I'm in therapy," he said. "Trying to do some public service. Working in a food bank. Working on a new book."

While it's true the incident amounted to a waking nightmare, let's be grownups here. With millions working from home for more than a year, a mishap like this was bound to happen.

Toobin was doing, in what he thought was a private moment, something we consider in 2021 to be healthy and normal, at least in moderation. As a matter of fact, there's evidence sexual release helps overcome writer's block and enhances creativity.

So if Toobin didn't expose himself to his colleagues on purpose, why does he need to be in therapy? And why does he need to do penance by working at a food bank?

It's admirable that he's doing these things, but what he really needs, I think, is an hour with tech support.

There are other mitigating factors to consider in Toobin's case as well.

By October, when the call took place, we'd all been in lockdown for about six months, and life had pretty much become a Stephen King novel, so much so that King himself said this: "I'm sorry."

Last fall, when I saw the first New York Times headline about the Toobin incident, it didn't strike me as another case of #MeToo. My first thought was that the solitude of quarantine was driving people batty.

"Dear God, the wheels are coming off," I muttered as I read The Times' story.

The Toobin situation was an object lesson of the pandemic's bombshell-like disruption: Isolation, shattered routines, constant stress and woefully blurred lines between work and personal life.

People's homes had become like submarines deep at sea, and Zoom and Microsoft Teams were the only portals through which we saw the outside world — and through which the outside world could see into our lives.

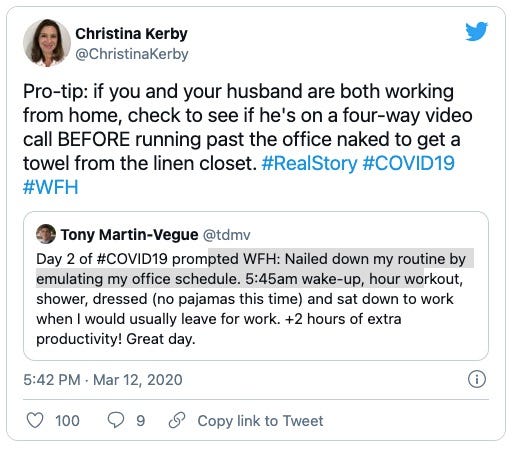

Of course these problems reached far beyond The New Yorker. One woman reportedly took her laptop to the bathroom during a meeting, but forgot to turn off the camera. Another woman emerged from the shower and streaked her husband's video call on her way to the linen closet for a towel. A far more intentional transgression: During last year's first day of online learning, a Seattle middle school student dropped a porn link into a Teams chat that included hundreds of students. Mayhem ensued.

Meanwhile, the booze aisle at the SoDo Costco was regularly pillaged. People wearing torn sweats and their old Duran Duran t-shirts sent emails late into the night while devouring microwavable lasagna and sipping Chablis. Xanax and Valium use spiked. And employers started talking about their workers' mental health in a way they never had. In fact, Microsoft gave its employees an extra week off, just to keep them sane.

If office life had once resembled "Downton Abbey," working from home had become "Beyond Thunderdome." People may have kept their game faces on, but we all knew it was getting a little ragged behind the scenes.

All of this context matters when we're talking about what Toobin did.

At the very least, I think Toobin should have waited until he knew his colleagues were offline. He could have slapped a sticky note over his webcam or aimed it at the ceiling. He could have gone into another room, safely out of view of his work laptop. If he was getting saucy with someone online, he could have logged on via his phone or iPad instead of what I presume was his work computer. All of this would have prevented the situation that ended his New Yorker career.

In addition, one could argue that all of us working from home during the pandemic shouldn't do anything we wouldn't do at the office. Strict eight-to-five hours. No cat naps. And certainly nothing like what Toobin did.

But rare is the person with that kind of discipline, especially for 18 months and counting. And you can't tell me that couples stuck working from home together didn't occasionally rendezvous midday to blow off a little steam.1

Even as he acknowledged he was in the wrong, Toobin said he thought The New Yorker's decision to fire him "was excessive." I agree. And so does Tina Brown, the former New Yorker editor who hired Toobin.

“I think 27 years of superb reporting and commitment to The New Yorker should have been weighed against an incident that horribly embarrassed the magazine but mostly embarrassed himself,” Brown told The New York Times.

Longtime New Yorker contributor and author of many books Malcolm Gladwell told the Times he also didn't understand the magazine's decision to fire Toobin.

“I read the (New Yorker parent company) Condé Nast news release, and I was puzzled because I couldn’t find any intellectual justification for what they were doing. They just assumed he had done something terrible, but never told us what the terrible thing was," Gladwell said. "And my only feeling — the only way I could explain it — was that Condé Nast had taken an unexpected turn toward traditional Catholic teaching.”

The Times reporter wrote that Gladwell then produced a Bible and read aloud from Genesis 38, in which God "strikes down a man for succumbing to the sin of self-gratification.”

In fact, experts expected a pandemic baby boom. It's yet to arrive, not because people didn't get together, but because they chose not to conceive when they perceived the world to be such a mess.

Get in touch! Feel free to reach me at tlystra@satellitenw.com.